Elusive silver eel migrations detected in the Chesapeake mainstem for the first time

Note: This short essay was originally posted in the December 2022 Chesapeake Biological Laboratory newsletter.

When Sheila Eyler of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) tagged 16 American eels 75 miles upstream of the Conowingo Dam she knew where they might end up – in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in the Sargasso Sea – but whether they could traverse the major dams of the Susquehanna and how they would get there were still mysteries. Detections provided by the Chesapeake Biotelemetry Backbone, funded in part by the JES Avanti Foundation, have shown for the first time how these eels migrate out of the Bay.

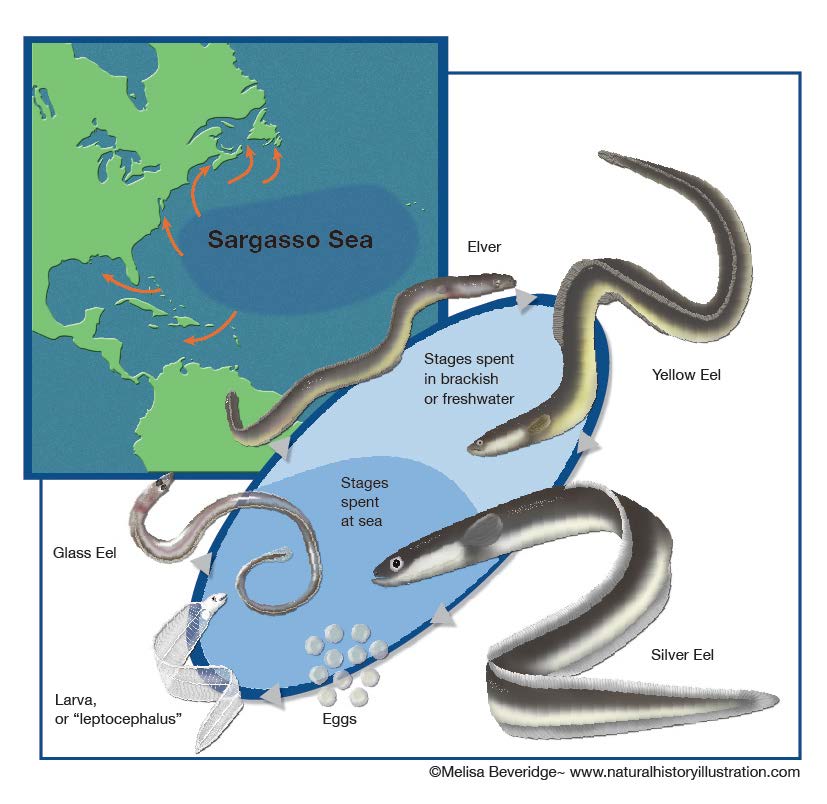

American eels are born in the Sargasso Sea, hatching into transparent leptocephalus larvae while riding ocean currents into the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The larvae transform into glass eels and migrate upstream, where they live and grow as yellow eels for 5-20 years. When the eel is ready to spawn, they stop eating and turn into silver eels for their terminal trek back to the Sargasso Sea. Where, exactly, they go in the Sargasso is still unknown; when they spawn is only inferred from the presence of larvae.

Identifying when silver eels leave the Chesapeake may shed some light on this mysterious migration. For many years, we assumed the eels migrated between August and November – it’s when scattered silver eels appeared in pots and pound nets and it’s when they’re known to migrate in New England. However, it now looks like silver eels leave the Chesapeake during winter months. As is the case with other unexpected discoveries (see Atlantic sturgeon: Not the ‘ghosts’ I once thought they were, Bay Journal 2021), we were looking in the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong tools.

Enter the Chesapeake Bay Biotelemetry Backbone: a broad partnership between the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. The team aims to deploy biotelemetry arrays in a sustained, year-round manner that covers major portions of the Chesapeake Bay. Each array is located near “pinch-points” in the Chesapeake, chosen to maximize chance encounters with electronically tagged fish. Most importantly, the array is constantly listening for fish – even through the cold winter months – and does away with the need to directly capture fishes such as the cryptic silver eel.

In the first year of Eyler’s eel tagging, the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory’s backbone array detected five tagged Susquehanna eels passing by the mouth of the Patuxent River, MD. The silver eels blew by on their way to tropical Sargasso latitudes in the dead of winter – between late-December and mid-February – rather than fall months as in New England. Further, their stalwart migration emerging from the Conowingo and other major dams is good news for conservation efforts to restore American eels to the Susquehanna River. With USFWS planning to tag 200 more silver eels in the next 2 years and sustained deployment of the Chesapeake Bay Biotelemetry Backbone, knowledge of the timing and extent of Chesapeake silver eel migrations will only increase.